First Scouts in Antarctica

Scouts have a longstanding tradition of contributing to Antarctic exploration and scientific research, embodying the organization's values of leadership, resilience, and service. From early 20th-century expeditions to contemporary scientific missions, Scouts have participated in and supported endeavors that have advanced our understanding of the Antarctic region. The following pages provide detailed accounts of these significant contributions, highlighting the impactful roles Scouts have played in the history of Antarctic exploration and science.

1911 Australasian Antarctic Expedition

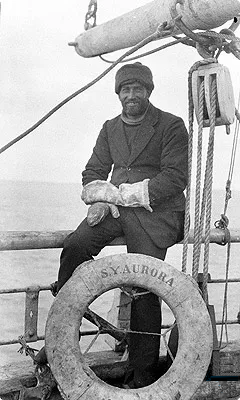

Charles Hoadley, a pioneering Australian Scout leader, holds a unique place in the history of both Scouting and Antarctic exploration. As one of the founders of one of the earliest Scout Groups in Footscray, Victoria, Hoadley believed deeply in the values of service, leadership, and adventure. Those same qualities led him to become a key member of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) led by Sir Douglas Mawson from 1911 to 1914.

Hoadley served as a member of the Western Base Party, one of three groups tasked with exploring different sectors of the largely uncharted Antarctic coast. The Western Base team faced some of the harshest conditions imaginable, conducting geological and scientific surveys while enduring brutal weather and isolation. Hoadley’s dedication, resilience, and scientific contributions were essential to the success of the expedition.

In recognition of his service, Cape Hoadley — a prominent coastal landmark in East Antarctica — was named in his honor by the expedition team. Hoadley’s legacy lives on not only in the icy landscapes of the southern continent, but also in the generations of Scouts he inspired. His life is a powerful example of how Scouting and scientific exploration can go hand-in-hand, rooted in the same spirit of courage, curiosity, and commitment.

1921 Shackleton–Rowett Expedition

In 1921, Sir Ernest Shackleton embarked on the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition aboard the ship Quest. Notably, he invited two Boy Scouts, James William Slessor Marr and Norman Erland Mooney, to join the voyage, selecting them from over 1,700 applicants — a testament to the prestige of Scouting at the time.

James Marr, an 18-year-old from Aberdeen, Scotland, eagerly accepted the challenge and became an integral part of the expedition. In contrast, Norman Mooney, just 16 years old, fell ill during the voyage and disembarked at Madeira, unable to continue.

The expedition faced significant challenges, including the untimely death of Shackleton in South Georgia in January 1922. Despite this, the team continued under new leadership, and Marr played a role in the subsequent activities.

These events underscore the profound impact of Scouting during the era, offering young individuals unparalleled opportunities for adventure and personal growth.

1928 First Byrd Antarctic Expedition

In 1928 to 1930, Admiral Richard E. Byrd embarked on his first Antarctic expedition with the goal of advancing scientific exploration and achieving the historic feat of flying over the South Pole. To inspire youth involvement and underscore the expedition’s spirit of adventure, Byrd announced his intention to include a Boy Scout in the journey. This initiative led to a nationwide search among Eagle Scouts, culminating in the selection of 19-year-old Paul Allman Siple from Erie, Pennsylvania.

Siple’s selection was the result of a rigorous process that evaluated candidates on their health, character, and ambition — qualities deemed essential for the expedition’s success. Admiral Byrd emphasized the importance of these attributes, stating that he sought someone who would make a vital contribution to the happiness and success of the mission. Among the six finalists, Siple stood out not only for his exemplary scouting achievements but also for his enthusiasm and resilience, which resonated with both his peers and the selection committee. One of the deciding factors was that Siple had earned both the Carpentry and Taxidermy merit badges, skills that Byrd considered to be essential during the planned expedition.

Siple’s inclusion in the expedition marked the beginning of a distinguished career in polar exploration. He went on to participate in six Antarctic expeditions, contributing significantly to scientific research in extreme environments. Notably, he co-developed the concept of wind chill, a critical factor in understanding human adaptability to cold climates. Siple’s journey from Eagle Scout to esteemed Antarctic explorer exemplifies the profound impact that scouting values and early opportunities can have on shaping future leaders in exploration and science.

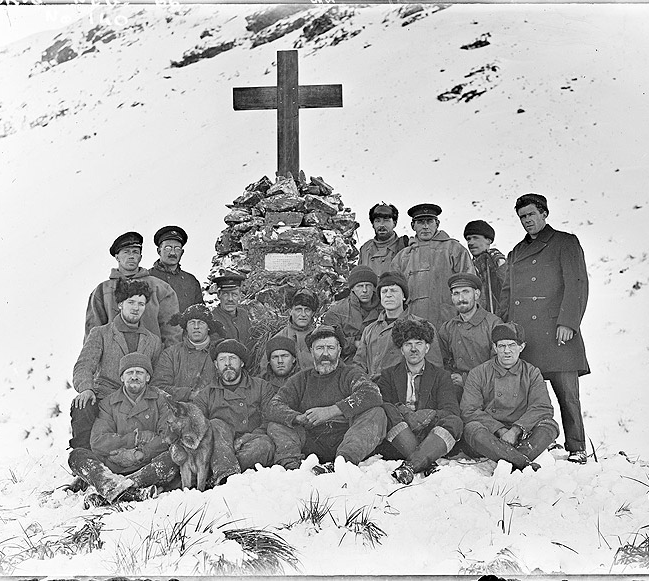

1934 British Graham Land Expedition

The British Graham Land Expedition (BGLE) of 1934–1937 was a pivotal mission in Antarctic exploration, aiming to conduct extensive geographical and scientific research in Graham Land, the northern portion of the Antarctic Peninsula. Led by Australian explorer John Rymill, the 16-member team comprised young and enthusiastic explorers, scientists, and military officers. Despite operating on a modest budget, the expedition achieved significant milestones, including the mapping of over 1,000 miles of Graham Land’s coastline and the confirmation that Graham Land was a peninsula, not an island as previously thought.

The expedition utilized a blend of traditional and modern techniques. They employed dog sleds and motor sledges for overland travel and used a de Havilland Fox Moth aircraft for aerial surveys. Their vessel, the Penola, an aging three-masted sailing ship with an unreliable auxiliary engine, was supported by the Discovery II, which transported additional supplies, including dogs and aircraft.

Among the expedition members was James William Slessor Marr, a Scottish marine biologist and former Boy Scout who had previously accompanied Sir Ernest Shackleton on the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition in 1921. During the BGLE, Marr conducted extensive studies of marine life, contributing valuable specimens and data to the scientific community. His work during this period laid the foundation for his later leadership of Operation Tabarin during World War II, which established a continuous British presence in Antarctica.