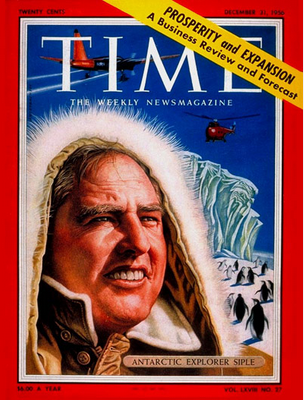

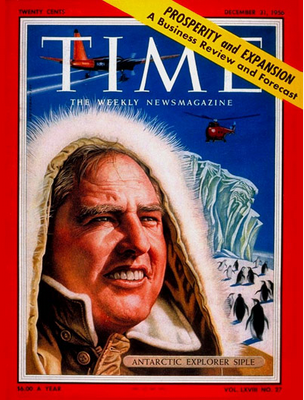

1945 Wind Chill Factor

Paul Siple, the Eagle Scout turned polar explorer, made lasting contributions to science beyond his early adventures with Admiral Richard Byrd. One of his most influential achievements was the development of the wind chill factor, a concept that helps us understand how cold weather actually feels to the human body. While conducting experiments during his time in Antarctica, Siple studied how quickly water would freeze in different combinations of temperature and wind speed. These experiments led him and fellow researcher Charles Passel to quantify the rate of heat loss from the human body in cold, windy conditions.

Their work introduced the wind chill index, which describes the combined effect of cold air and wind on exposed skin. This index has since been refined but remains fundamentally based on the research Siple began in the polar regions. Today, the idea lives on in the weather reports we check every winter — when we see “feels like” next to the actual temperature, that’s wind chill in action. Thanks to Siple’s pioneering work, people around the world have a better understanding of how to stay safe and dress appropriately in cold weather — an everyday legacy born from extreme exploration.

Paul Siple and Charles Passel first introduced the concept of wind chill during the Second Byrd Antarctic Expedition (1939–1941), but their formal publication of the wind chill index came in 1945. Their research was published in the paper titled:

“Measurements of Dry Atmospheric Cooling in Subfreezing Temperatures” in the journal Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

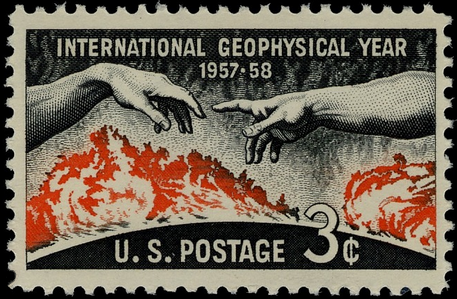

1957 International Geophysical Year

Eagle Scout Paul Siple played a key leadership role during the International Geophysical Year (IGY), serving as the first scientific leader at the U.S. Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, which was established in 1956 specifically for IGY research. His leadership helped shape one of the most ambitious and collaborative scientific efforts of the 20th century.

The International Geophysical Year (1957–1958) was a massive, multinational scientific campaign involving over 60 countries and thousands of scientists. The goal was to advance understanding of Earth’s physical properties — spanning glaciology, meteorology, oceanography, seismology, geomagnetism, and more — with a special focus on the polar regions. Antarctica, long isolated and underexplored, became a central stage for this global effort.

Siple oversaw operations and scientific programs at the South Pole during a time when simply surviving in the extreme conditions was a feat in itself. Under his leadership, the team conducted groundbreaking research in atmospheric science, cosmic rays, and geophysics — laying the groundwork for modern climate science and space weather forecasting. His ability to bridge the roles of explorer, scientist, and leader made him uniquely suited to guide the U.S. presence during this historic moment in Antarctic exploration.

The IGY was a remarkable success, leading to major scientific discoveries, including confirmation of plate tectonics, increased understanding of the Van Allen radiation belts, and a vastly improved global network of weather and seismic monitoring. It also paved the way for peaceful international cooperation in Antarctica, directly leading to the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, which protects the continent for scientific and peaceful purposes to this day. Paul Siple’s leadership during the IGY helped not only to advance science, but also to cement Antarctica’s role as a place for global collaboration and discovery.

The International Geophysical Year (IGY) of 1957–1958 was a landmark example of global scientific cooperation during the Cold War. A total of 67 countries participated in the IGY, setting aside political tensions to advance knowledge about the Earth and its atmosphere. The IGY marked the first time many nations came together to conduct coordinated, worldwide research in fields like geophysics, meteorology, oceanography, and space science.

Notable participating countries included:

United States • Soviet Union (USSR) • United Kingdom • France

Japan • Argentina • Australia • Canada • Chile • South Africa

New Zealand • Norway • Germany • India • Italy • Brazil

United States

Soviet Union (USSR)

United Kingdom • France

Japan • Argentina • Australia

Canada • Chile • South Africa

New Zealand • Norway

Germany • India • Italy • Brazil

Despite Cold War tensions, both the U.S. and the USSR made major contributions, including launching the first artificial satellites (Sputnik 1 by the USSR and Explorer 1 by the U.S.) — ushering in the space age. The IGY also saw unprecedented cooperation in Antarctica, with 12 countries establishing more than 50 research stations across the continent.

This spirit of peaceful collaboration led directly to the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, ensuring Antarctica would be used exclusively for scientific and peaceful purposes — a legacy of the IGY that continues to this day.

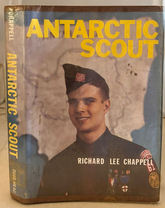

1957 Richard Chappell

Richard Chappell, an Eagle Scout and one of the few Scouts to follow in Paul Siple’s footsteps, played a significant role in Antarctica during the late 1950s. In 1957, at just 18 years old, Chappell was selected from a national competition to serve as the official Scout representative during the International Geophysical Year (IGY). Much like Siple a generation earlier, Chappell’s appointment symbolized the close connection between Scouting and the spirit of exploration, service, and science. His selection was part of a broader effort to involve youth in international scientific cooperation and to inspire a new generation of explorers.

Chappell served at Little America V, the U.S. base on the Ross Ice Shelf, during the early years of the U.S. Antarctic Program. He contributed to logistical and scientific support operations, working with the team to maintain camp life and assist in scientific fieldwork. Although he was not a senior scientist, his presence was both symbolic and functional — demonstrating that young people could meaningfully contribute to even the most remote and demanding expeditions.

After his return, Chappell remained a passionate advocate for science and Scouting, often speaking publicly about his Antarctic experiences and their impact on his life. His journey helped keep alive the legacy of youth involvement in polar science, showing that Paul Siple’s precedent was not a one-time event but the beginning of a tradition. Chappell’s service in Antarctica during such a historic moment in global cooperation stands as a proud chapter in the story of Scouting’s contributions to polar exploration.